Terminology

A brief account of Rabbi Gaguine’s operational definitions will help the reader understand how he subdivided the Jewish community in his treatment of this material:

The Jews of London and Amsterdam: this is how Rabbi Gaguine refers to Spanish and Portuguese Jews, also known as “Western Sephardim,” whose most famous communities are located in these capitals. Thriving originally in Iberia while it served as a center of world Jewry, this group was permanently transformed by the shared experiences of expulsion, crypto-Judaism, and reconstruction. After emigrating to more hospitable countries in Western Europe, the Caribbean, and North America, members of the self-styled “Portuguese Nation” confidently reestablished themselves as living communities and invited their converso brethren to follow in their footsteps. In the process, they combined ancient Iberian traditions, Hispanic cultural attitudes, and Western music and values into an original new culture to which they adhered with a dignified conservatism that both helped and hindered their continuous survival until today.

The Jews of Syria, Egypt, and Togarma: this is how Rabbi Gaguine refers to the Jews of the Middle East, North Africa, and the Turkic speaking territories, also known as “Eastern Sephardim.” Prior to the late 14th century, these regions were home to long-established populations that were neither Ashkenazic nor Sephardic, and which followed their own minhagim and legal methodologies. However, when Iberian refugees and expellees began to flow eastward by the tens of thousands, they brought Sephardic laws and customs with them and missionized the local communities to accept their usages. The result was a cultural fusion, in which Sephardic liturgical rites and halakhic approaches predominated even as the individual Sephardim were integrated into indigenous society and lost their sense of affiliation with the “Portuguese Nation.” This process is the origin of using the word “Sephardic” to apply to an ever-widening circle of Jews outside Europe, to the point where it is now a vague umbrella term that simply means “non-Ashkenazic.”

The Jews of the Land of Israel: Rabbi Gaguine frequently includes this group as part of the previous one, referring them together as 'the Jews of E"Y and ST"M' [i.e. Erets Yisrael veSuria Togarma Mitsrayim]. However, he sometimes singles them out for special comment, a role in which he was fully qualified as an eyewitness of that community. When this happens, he often skews toward the practice of Jerusalem, the city of his birth.

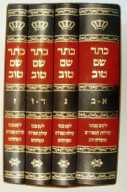

Ashkenazim: Rabbi Gaguine usually speaks about this group in monolithic terms, although he occasionally cites specific regions or cities. This is a reflection of the general thrust of Keter Shem Tob, which treats Sephardim in equally wide meta-categories. The book devotes a lot of energy to variations in liturgy and halakhic approach, which are more likely to be shared across broad areas than the many individual minhagim that make up the remainder of the work.

Other: Jews that cannot be classified as historically Sephardic, liturgically Sephardic, or Ashkenazic are mostly outside of the scope of the Keter Shem Tob. Thus, Italian, Romaniote, Ethiopian, Yemenite, Persian, Central Asian, Chinese Jews, etc. appear rarely, if at all. South Asian Jews receive a more sustained treatment because The Jews of Cochin was appended to the seventh volume when it was published by Rabbi Gaguine’s son Maurice in 1981.

Back to "About the Book"

The Jews of London and Amsterdam: this is how Rabbi Gaguine refers to Spanish and Portuguese Jews, also known as “Western Sephardim,” whose most famous communities are located in these capitals. Thriving originally in Iberia while it served as a center of world Jewry, this group was permanently transformed by the shared experiences of expulsion, crypto-Judaism, and reconstruction. After emigrating to more hospitable countries in Western Europe, the Caribbean, and North America, members of the self-styled “Portuguese Nation” confidently reestablished themselves as living communities and invited their converso brethren to follow in their footsteps. In the process, they combined ancient Iberian traditions, Hispanic cultural attitudes, and Western music and values into an original new culture to which they adhered with a dignified conservatism that both helped and hindered their continuous survival until today.

The Jews of Syria, Egypt, and Togarma: this is how Rabbi Gaguine refers to the Jews of the Middle East, North Africa, and the Turkic speaking territories, also known as “Eastern Sephardim.” Prior to the late 14th century, these regions were home to long-established populations that were neither Ashkenazic nor Sephardic, and which followed their own minhagim and legal methodologies. However, when Iberian refugees and expellees began to flow eastward by the tens of thousands, they brought Sephardic laws and customs with them and missionized the local communities to accept their usages. The result was a cultural fusion, in which Sephardic liturgical rites and halakhic approaches predominated even as the individual Sephardim were integrated into indigenous society and lost their sense of affiliation with the “Portuguese Nation.” This process is the origin of using the word “Sephardic” to apply to an ever-widening circle of Jews outside Europe, to the point where it is now a vague umbrella term that simply means “non-Ashkenazic.”

The Jews of the Land of Israel: Rabbi Gaguine frequently includes this group as part of the previous one, referring them together as 'the Jews of E"Y and ST"M' [i.e. Erets Yisrael veSuria Togarma Mitsrayim]. However, he sometimes singles them out for special comment, a role in which he was fully qualified as an eyewitness of that community. When this happens, he often skews toward the practice of Jerusalem, the city of his birth.

Ashkenazim: Rabbi Gaguine usually speaks about this group in monolithic terms, although he occasionally cites specific regions or cities. This is a reflection of the general thrust of Keter Shem Tob, which treats Sephardim in equally wide meta-categories. The book devotes a lot of energy to variations in liturgy and halakhic approach, which are more likely to be shared across broad areas than the many individual minhagim that make up the remainder of the work.

Other: Jews that cannot be classified as historically Sephardic, liturgically Sephardic, or Ashkenazic are mostly outside of the scope of the Keter Shem Tob. Thus, Italian, Romaniote, Ethiopian, Yemenite, Persian, Central Asian, Chinese Jews, etc. appear rarely, if at all. South Asian Jews receive a more sustained treatment because The Jews of Cochin was appended to the seventh volume when it was published by Rabbi Gaguine’s son Maurice in 1981.

Back to "About the Book"